Insomniac Magazine’s interview with former Def Jam publicist and music industry executive Bill Adler. An inside look into Hip Hop history.

Story and interview by Israel Vasquetelle

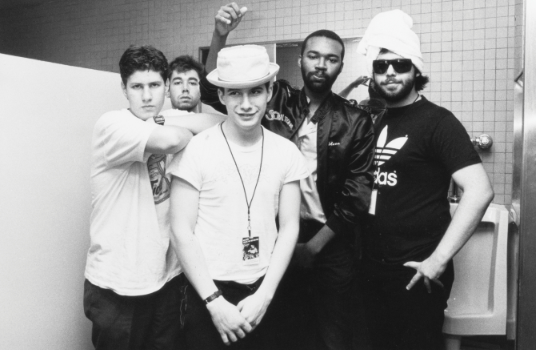

[Run DMC and Aerosmith and Bill Adler (rear) (courtesy of Rizzoli)]

I first spoke with Bill Adler in the ’80s when I was just a kid trying to get insight into the entertainment industry. I would call the label that he worked at, and he’d take the time to talk. Decades later, in this interview, Bill continues to generously share. What’s changed since those early days is that the nascent genre of music he worked on building awareness for so long ago has since become one of the most popular in the world, and immensely important economically to the whole of the music industry. Culturally, the label Adler helped build awareness for so many years ago, has become one of the most powerful and important due to its roster of iconic artists that are known to millions. As Head of Publicity, first for Russell Simmons’ Rush Productions, and then, upon its inception, for Def Jam, Adler’s role was vital in helping to get the word out to the universe about up and coming superstars such as Run DMC, LL Cool J, The Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, Slick Rick, and countless others. Although the man who also served as Vice President of Media Relations for Island Records is quite humble when asked about his great undertakings, it’s clear that proper presentation to media outlets about the story of each of these (at the time) new artists, in a genre that wasn’t quite accepted as a legitimate music, was an immensely important part in the launching of their careers.

Def Jam Recordings: The First 25 Years of the Last Great Record Label, a book that Adler co-authored to help tell the oral and visual story of Hip Hop’s most prominent record label, provides amazing insight from a who’s who of important players. From founding partners Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin, to many of the company’s key executives, and even the legendary artists themselves, this book provides a wealth of first-hand accounts of those early days of Def Jam, and, in many ways, the genre itself. Visually, the book is comprised of some of the most amazing photographs of Def Jam’s vital players, truly giving an inside historical perspective of the label that helped shape and introduce Hip Hop to the mainstream.

Legendary in his own right, in this in-depth and candid interview, Adler discusses this impressive new book, while openly providing a distinct glimpse into the early days at the label. He shares his great wealth of knowledge about music, media, and his experiences working with Hip Hop’s most celebrated record label from its infancy to the dominance of pop culture globally. Let’s begin:

I: If we could go back toward the beginning and talk a little bit about your first encounter with Russell and Rick.

BA: I met Russell first. Really, I was an employee of…Rush Productions before I was an employee of Def Jam, and that’s only because I started working with Rush just a few months before the establishment of Def Jam. The first Def Jam records came in the fall of ’84 and I was working with Russell at Rush Productions in late June of ’84. I met Russ because I was a freelance writer in New York in the early ‘80’s…in the fall of 1980, I did a story for the Daily News about Kurtis Blow who had a national hit called “The Breaks” and I started to hear at the time about Kurt’s manager, a young man named Russell Simmons. In early ’83 I did a story for People Magazine about Disco Fever in the Bronx, and it was Russ who put me on to Disco Fever. That wasn’t supposed to be the crux of the story. It wasn’t supposed to be the subject of the story. I was going to do something more broad, more general, but that place was so compelling I said well I’ll tell the story about Hip Hop by concentrating on this one venue and this one kind of energy center.

In any case, Russell then was, not unlike the way he is now, it’s just that he knew less people. You know, Russell is a world-beatingly charming. He’s got blazing charisma, blazing intelligence, a great sense of humor, and was animated by the sense of mission which was to do work on behalf of this emerging culture called Hip Hop. So he made a big impression on me in ’83 and I stayed in touch with him. Then in ’84, it was going to be a presidential election and Ronald Reagan was up for reelection, and I was not a fan of Reagan, and my idea was well you know I’m trying to think of my own little way, what can I do to derail his presidency or forestall his getting reelected. What I did was I wrote a rap. An anti-Reagan rap and I wrote it with Kurtis Blow in mind because Kurt didn’t write all of his own rhymes. So I thought well, I’ll write it and Kurt can rap it, and I brought it to his manager namely Russ. The two of us get to talking and I don’t think he thought much of my rhymes, but he liked me well enough and the two of us got to talking. He kind of flattered me into a job, and so I started working with him.

BA: Then it was after that that I met Rick; very shortly after I started working with Russ, I met Rick.

I: Please talk to me a little bit about possibly your first encounter with Rick, and what was your first impression of Rick?

BA: Rick Rubin-I don’t remember my first encounter per se. The thing about Rick is that even then he was relatively reclusive. When I first met him, he was still a student at NYU and living in a dorm there. Not long after, within a year, he moved out and he took a place in Lower Manhattan. He never had an office, and he never kept office hours. He was basically a studio rat; then and now. That’s really kind of how and where he spent his life, in recording studios. It sort of the same now, he shuttles between his lovely house in Malibu and various studios, and of course he’s got studios built into his place in Malibu. I will say this in terms of his demeanor, he was much-as the book says. [In the book] Adam Horowitz talks about Rick’s demeanor then. Rick’s basic style was kind of very much taken or inspired by professional wrestling, and characters like Captain Lou Albano, which is to say that he was a screamer and he was loud and aggressive in a kind of comical way. That’s how he was then. He’s not that way now. Now he’s gone 180 degrees in the other direction. He’s very soft spoken… But that’s the way he was then.

I: Right. Let’s talk a little bit about Hip Hop. You mentioned Kurtis Blow; obviously one of the forefathers of Hip Hop and definitely one of the first artists to make a significant name for himself and professionally recordings in the Hip Hop genre. What attracted you to the genre at the time and what were you listening to before you got involved in Hip Hop?

BA: I can’t be coy about this. I’m about to turn 60 years old. In December I’m going to be 60, and by the time I started working with all these Hip Hopers, I was already in the summer of 1984 I’m already 32 years old. So I’m six years older than Russell, I’m whatever it would be, nine years older than Rick. When I started working in ’84, Run DMC those guys are 19 and 20 years old, LLCool J signs up he’s 16. I’m much older than everybody that I’m working with. It’s not surprising to understand that I’ve got a history that pre-dates Hip Hop. I was a music lover. I started playing trombone as a ten-year-old in a band, and then I was magnetized by the Beatles when they hit in ’64. I was swept up by the music of the day like anybody else. I think probably I felt a little more passionately because really music has been my life ever since. I’m a ‘60’s guy. By the early ‘70’s, when I’m in my early 20’s, I had worked on the radio… Almost every job I ever had was kind of music related.

I worked as a clerk and then a manager at a record store. I worked as a DJ for college radio and then professionally. I started writing about music and that seemed to gain me a little traction. So I worked for an underground newspaper in Ann Arbor, and then I took a job full-time at the Boston Herald in Boston as the pop music critic. I was writing about whatever struck my fancy. In effect, I was my own editor. My tastes were very broad. Broad enough to do that job, so I was going to pay attention to what was happening pop-wise, but I was also going to write about the jazz of the day or stuff that wasn’t current necessarily or stuff that was left field that struck my fancy. During that time, so 1979 and I’m in Boston and I’m paying attention to what’s going on, and “Rapper’s Delight” comes out that fall and it was phenomenal. It was a great, great record but also it seemed to mean more than the record itself because it was a little bit different…in other words in terms of genre because nobody was singing. You know they were rapping, and also the thing was fifteen minutes long.

There was a three-minute edit but nobody bothered to play it on the radio. Every single time you heard it on the radio, the entire fifteen-minute song was played which was completely remarkable. I dug it, and I bought it and I started listening to it. I moved to New York July 1, 1980. And by that fall I was freelancing and because I’d dug Sugar Hill Gang, I noticed when Kurt had his hit. Actually what happened was I was still in Boston when he put out a “Christmas Rappin’”. “Christmas Rappin’” was a remarkable record because you didn’t hear it until ten minutes before Christmas. Somehow it just entered the market kind of late and they were still playing it in March; a Christmas song. Just because it was so magnetic. This stuff was so intrinsically sexy. A year later I’m in New York and Kurt has the Breaks, and I went to the Daily News and persuaded them to do a story about Kurtis and so it went on from there.

The Hip Hop and Punk music connection.

I: What do you think it is the kinship between those Hip Hop and Punk music? People like [Malcolm] McLaren and the Clash and Blondie. That has dissipated. There was somewhat of a bond, if nothing else, in the spirit of the music that I don’t see today. Can you address that?

BA: What happened was the two scenes were very small, and they were kind of sub-cultural. It seems to me on both sides that divide, the Punk Rock and Hip Hop side there were a very few forward thinking individuals who were able to bridge the divide. On the Hip Hop side somebody like Fab 5 Freddie who had the social range to hang out at CBGB’s as well as uptown and downtown at the Hip Hop spots. He was going to imagine similarities between two cultures and make friends on both sides of that divide. On the Punk Rock side, it seems to me it was mostly English people who were able to make a kind of connection. So you had McLaren, and McLaren was put on to it by Cool Lady Blue and maybe Michael Holman somehow. My friend Janette Beckman is an English photographer who moved to New York in ’83 or so, and she’d documented the Punk Rock scene and then kind of emerging New Wave scene in London up until that time when she came to New York, and kind of began to become exposed to this new Hip Hop scene, she thought that the similarities were a kind of rebelliousness. I guess a kind of like a “fuck you” attitude in both cultures that tied them together in her mind.

I: Obviously the Beastie Boys seemed to have seamlessly moved from one genre to the other, almost effortlessly.

BA: Well that’s because Horowitz talks about that. Just that in the downtown clubs at that time the DJs-there was no kind of strict respecting of the genre. Radio was so corny at the time. It was so straight-laced. Each format was, I called it box but it was more like a coffin. But if you were in downtown New York at the time, you could hear Punk Rock and you’d also hear the rap records that were being played then. The jocks had that kind of range. They could program that kind of music, side by side. It wasn’t discomforting, it wasn’t disconcerting, it wasn’t disjunctive, it made sense. And Horowitz was just a little teenager going to the parties, underage, and listening to it and absorbing it all. It certainly didn’t seem remarkable to him because it was just part of the mix. Along these lines, let me say something about [Afrika] Bambaataa. He is the archetypal Hip Hop DJ, which is to say he has gigantic ears, and he was also somebody who was no respecter of genre. He was a guy who looked for danceable funk in all kinds of music, and he would find it everywhere. Notably “Planet Rock” is built out of Kraftwork’s “Trans Europe Express.”

He made that work for himself. By 1981, he was a solidifying Hip Hop’s affection for rock, or Hip Hop cannibalizing of rock. In any case, he was no snob and he was no square. He was a guy who could hear…he was just somebody who liked all kinds of music which was basically the way musicians listen to the music anyway. The average consumer, I suppose somebody who’s dull, figures well I’m White and I’m going to like rock music or whatever these dark-skinned people do, that doesn’t speak to me. It’s a retarded kind of attitude, and likewise, there are Black folks who think if it’s rock-n-roll, these crazy white kids with their guitars and I don’t know what the hell they’re talking about, and fuck them. Mostly, if you’re a music lover, you’re going to find connections between all kinds of music. You’re going to follow those connections and you’re going to follow those leads, and your life is going to be enriched. How about that?

I: Indeed.

BA: Bambaataa had that attitude in spades and he really created the blueprint for every other Hip Hop DJ and Hip Hop producer in history. All of them come out of Bambaataa.

I: Obviously, Def Jam’s initial artists and first roster was definitely diverse, distinct, and unique, and tapped into so many different sounds. Do you think that we’ve kind of gone backward as a genre in regards to it now being very stereotypical? Do you feel that we’re back in that coffin? You’re not going to listen to urban radio and hear a punk record, yet back then, you might hear someone on WKTU mix something like Queen with a Grand Master Flash record. Do you think we’ve gone backward?

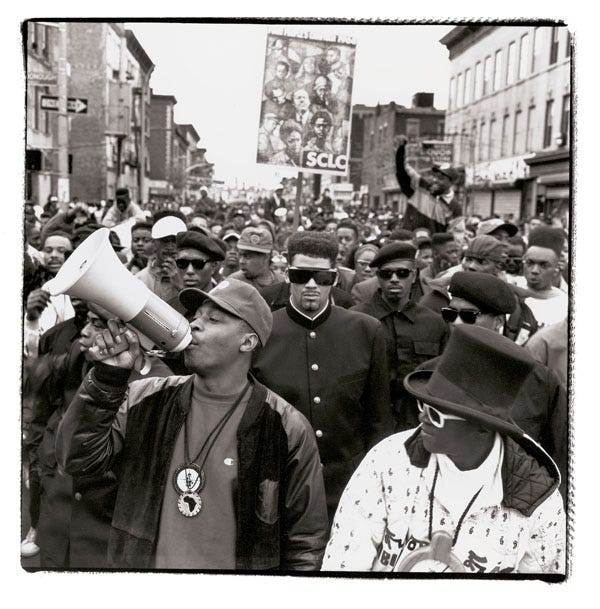

BA: I don’t know. I don’t know if I’m really the guy to talk to about that because I don’t study current Hip Hop the way that I used to study it. What occurs to me is this: Hip Hop remains very, very popular. I think that what one hears on the radio can be relatively one-dimensional, but I think there are all kinds of Hip Hop that are made and continued to be made, and all kids of hybrids that emerge all the time. Also, I’ll say this, one of the things that’s so thrilling to me is kind of a global impact, the ongoing global impact of Hip Hop. I don’t worry about a Rap Rock synthesis so much as I used to. What I know is if you go to Cuba, if you go to the Middle East, if you go to Africa, if you go to Asia, if you go to Russia, there are local rap scenes in all of these places. Rap in the native languages.

All of them, the reason that it can even emerge at all as a distinct expression of the local cultures is because it embraces and it’s built out of a local culture; inspired by this long ago culture that emerged out of Black New York for the most part. If it wasn’t being made now in the local language with local beats and expressing local concerns and all the rest of it, it wouldn’t mean shit. That’s not what’s going on.

I: That’s definitely a good point. Do you feel that Run DMC was a big part of that globalization of Hip Hop?

BA: Yeah. Let’s understand that whatever is going on with America politically and economically at this moment, as we’re on the phone today. All the pundits are scratching their head about America’s decline as an economic power and a political power. But culturally, for better or worse, that’s what we export. There is something about American culture, American music, and American movies, and American books, American television; these things remain a tremendously attractive to people all over the world. Influential to people all over the world. So that’s one thing and it was true back in the early ‘80’s as well. I’ll say this about Run DMC: they were very agile and energetic ambassadors of the new music, and they began touring right away that was one thing. They were the headliners on the very first national tours in ’84, ’85 and ’86. So that was one thing.

And there were always international legs to those tours, so they went to Europe and they went to Japan right away, and that stuff meant a lot. Also, they started making videos. By ’84 here’s Run DMC with “Rockbox” and it gets played on MTV. That helped them have a global impact. Listen, I’m going to talk about Run DMC because I worked with them and I love them, but let’s not neglect this: the very first hit rap record, “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugar Hill Gang comes out on a tiny little label, out of Englewood, New Jersey and it’s a huge international smash. You can look it up, but I believe it was top ten in at least a dozen countries. There was something about rap music from the very beginning that people all over the world seemed to love.

I: Do you feel that Run DMC was the first to put together a cohesive album in the genre? An album that pretty much every single track…

BA: Come on Israel that’s not a question, that’s a statement. That’s what you believe. I’m not going to disagree with you. I’ll tell you this: I think they were blessed to have Russell and Larry Smith working with them. I think they came into a very high standard because I believe they wanted to make every single mean something, and when it came time to assemble an album they cared more about the album as an art form than the people at Sugar Hill. They key thing was that at Sugar Hill, none of those artists had management. They certainly didn’t have effective management. What they had were record contracts. The people at the label, Joe and Slyvia Robinson, wonderful people, great record people, but they didn’t have an interest in building artists’ careers. They had an interest in making records. There was no album genre then. It was basically a singles genre, and so they made singles.

By the time Run DMC comes along, Russell, he only cut a singles deal with Cory Robbins’ Profile, and they put out three singles. The singles are doing well enough so Cory said let’s make an album. That’s kind of forward looking for Cory, that’s a good thing. And then it’s Run and Larry and the guys themselves, kind of well if we’re going to make an album, let’s make it as strong as possible from beginning to end.

I: You mentioned Sugar Hill and Profile, what was it do you feel about Def Jam that had that brand recognition from the early days, that people would follow the label?

BA: Here’s what happened I think. I think that that whole first generation, the first wave of rappers say between ’79 and the rise of Def Jam in ’84. You look at them now and they’re transitional figures. Def Jam was baptized in Hip Hop. Rick was somebody who was a huge lover of live rap, live Hip Hop and he was dissatisfied with the rap records that were being made. He thought that they were kind compromised. He said look you go to a club and it’s a DJ and he’s playing records and he’s scratching records. You listen to a Sugar Hill record and it’s a house band playing live and some rappers are rapping over that live beat. That’s kind of a holdover from an earlier era. He says where’s the DJ, where’s the scratching?

So that’s what motivated him to start making records. He said listen, “if nobody else is going to do it, I maybe a 21 year old college kid, but I’m going to do it. I’ll do it!” So that devotion to what he saw as one of the distinguishing characteristics of Hip Hop, defined the label. He was also a guy who cared about the visual side of it. So he was going to make a unique logo. He was going to sweat the details when it came to the artwork on the album. He’s going to pay attention to all these things. He poured his love and creativity into it in a way that had not been done before. He was child of the culture and the way the previous executives had not been. And of course Russell was the same way; Russell who’d been involved with the culture longer, not least because he was just whatever, five years older than Rick so he had bigger start on it, but he’s somebody who saw that it was in fact a culture. It’s not just a series of records. Russell is nine degrees short of a degree in sociology. He saw it in sociological terms. There’s a community here. There are people here. They happen to be young, it’s not just that they record in this way. They also dress a certain way. Like Rick or similar to Rick, he saw the visual impact or the visual importance of the culture. That was one of the things that Run DMC did that was unique. When it came time for them to get on stage, they weren’t going to be fantasy figures like Bambaataa or the Sugar Hill guys. They weren’t going to dress in this kind of half-assed, leftover funk style. They didn’t need to be Rick James, they didn’t need to be George Clinton, none of that. They were going to dress like street hustlers in Queens. They were going to dress like Jay, and that’s where Jay got his style. That was a very unique style already. It wasn’t the style outside of Black New York, but that’s what was going on in Black New York at the time and was fly as hell and Russell understood it. He took one look at Jay and said, “all right from now on you all are dressing like him.” That’s what he told D and Joe: “You’re dressing like Jay from now on.” So that’s the way they dressed.

The visual impact of the first album was incredible. Not just that this music was so remarkable, but the way these guys looked was unlike any rapper before them. Again, they’d been born in the culture, they represented the culture. It’s a new culture; there are new styles and Run DMC who did not record for Def Jam by the way.

I: Right. Of course.

They’re pure products of this new culture, likewise, it’s even truer of LLCool J who’s sixteen when he makes his first record; and Public Enemy, and Slick Rick and on and on. I think Def Jam cared not just about the records, they cared about the artists. They cared not just about the artists but they cared about the culture and they understood it to be a culture. With all of that going for them, what they did under the rubric of the label turned out to be very, very high quality and memorable.

I: Well said, and I think one of the biggest takeaways from what you said was that the folks that were making music before that, specifically the people that ran these companies, were music people, record people, but they weren’t Hip Hop people. And obviously, Def Jam was comprised of Hip Hop people.

BA: Yeah, that’s the difference. You’re right.

I: In many ways do you think that’s possibly one of the reasons why it was able to differentiate itself in a way that Tommy Boy, despite the fact they had amazing classic artists, wasn’t able to do as a label?

BA: I’m not sure. I mean, I will say this also: it turns out that Rick was a super talent. Rick was a world class producer, and you can’t discount that. Tom Silverman was not a producer. It’s very much to the label’s credit that Rick was behind the boards.

I: If you could talk to me a little bit about your first or your early marketing successes with Def Jam; getting them feature stories in publications, getting their artists on television, and getting them recognized in the media.

BA: It wasn’t difficult. I should probably say that it was the hardest thing in the world, but I think I was well suited. First of all let me say, I was well suited for the job because essentially I kind of worked in the pivot between press on one side and the artists on the other. By the time I start working and doing PR for these guys, I’d already been a working journalist for ten years and a working critic for ten years, so I’m somebody who knew how to talk the talk when it came to editors and writers. I thought in story terms. Then on the other side, I had the benefit of working day after day with the artists themselves and they were going to teach me about themselves, and Russell, to the extent that there were gaps in things that smacked me in the face that I didn’t understand, I would ask Russ and he would explain everything.

It never felt to me like an entirely difficult job. I’ll say this also: I always feel it was relatively easy for me compared to somebody like my friend Bill Stephney whose job it was to work Hip Hop to radio, to promote Hip Hop to radio. That was very, very hard because radio, by contrast, was much more closed minded, much more kind of genre-bound. When I’m talking to people at newspapers and magazines, even if it’s a music magazine, they just happened to be more open minded. Our guys were critical favorites right away. Somebody like Robert Christgau, who was the music editor at The Voice, was very, very influential. His open-mindedness was contagious. He put together a national critic’s poll year after year, and our guys started doing very well on that poll very early on. By the summer of ’84, not that I had anything to do with video promotion per se, but the so-called rock media were just open to us. Very early on in a way that the more conventional black media were not. MTV glommed on to us before BET did. Rolling Stone or even Life magazine liked us before EBONY did. Not to say that Right On magazine didn’t cover us right away, they did. I found that we had allies and confederates in the media from the very, very beginning and it tended to make my job pretty easy.

I: Do you think that today it would be a tougher thing to break a distinct or unique Hip Hop act just because of the fact that so much has been done already and it’s saturated? Do you think that a part of the fact that they were embraced because they were hip and new, and there wasn’t really much out there?

BA: No, I don’t. I think that it’s tougher for anybody these days just because there’s so much more product from all genres. I also think that one of the reasons that we were so successful at the beginning is because Russell understood that rap wasn’t just a kind of beat or it wasn’t a novelty. It wasn’t disco. Disco was producer’s music. The artists were interchangeable. Russell’s background was artist management, and so he understood that just because you bought a Run DMC record this week doesn’t mean you’re not going to buy an LL Cool J record next week. They’re different artists. They’ve got different appeal. They’ve got different skills and on and on. I believe that the same kind of considerations come in to play today. If you distinguish yourself one way or another as an artist with something unique to say and with unique appeal, and a ton of talent and luck, you’ll break through.

I: If we could talk about the diversity at Def Jam. Can you speak for a moment about Slayer’s entry into the label and how that was received both internally and also externally. I was a Hip Hop kid, I grew up in the Bronx, and to this day, I’m a fan of Slayer because I discovered them on the Def Jam label.

BA: Okay. That’s interesting. You should write that. By the time Rick kind of gloms on to Slayer, there’s already starting to be a split between Russ and Rick. All due credit to Rick, I was not a death metal head myself. It wasn’t appealing to me, and because I was really more Russ’ guy than Rick’s guys; it’s not like I felt constrained to work with them, and in fact the thing didn’t come out on Def Jam Columbia, it came out on Def Jam and Geffen I guess, and I wasn’t personally involved with it.

[Editor’s note: It’s reported that at the time, Columbia refused to distribute Slayer’s first release with Def Jam due to the controversial nature of Reign in Blood’s lyrics.]

I: I was always curious about Jimmy Spicer’s appearance on the Def Jam label. Obviously, he had records before that, but it was kind of interesting to have him on Def Jam and then he kind of disappeared after a string of hot records. Is there anything you can add?

BA: The records that he made before, with the exception of his very first record, were records that were produced by Russell and Larry Smith. The natural assumption was that he would make the transition with Russell from these other indie labels to Russell’s own label, Def Jam. Def Jam was independent for the calendar year from the fall of ’84 to the fall of ’85. At that time Rick and Russ were able to sign a deal with Columbia. I think maybe the second to last of seven singles released during Def Jam’s year of independence was Jimmy’s record. I don’t know; as I think about it maybe it was old fashion sounding. The important records, the impactful records were those singles by LLCool J and the Beastie Boys (it) was on the basis of their records that the deal with Columbia was signed, and they were new artists, they were artists that were kind of native to the label you could say, and Jimmy is somebody who was maybe a holdover from an earlier era. He just wasn’t able to cross over into the promise land.

I: In regards to Rush Management, they obviously managed some of the most iconic artists in the genre. Do you feel there were certain artists what could have benefited greatly or possibly would have had more longevity, if you will, if they were on the Def Jam label versus some of the other labels that they were on?

BA: Rick and Russ both of them dipped in the culture and committed to the culture. Rick brings this tremendous ability as a producer. Russell also a producer brings a real artist sensibility to it. He used to tell me we don’t make records, we build artists. That sensibility resulted, deliberately, as much as possible in relatively lengthy careers for the artists. The guys at the label were doubling as artist managers but also they think of terms of extending the career of an artist.

I: In regards to some of the Def Jam artists that have been released throughout the years, do you feel in those early years that they were underrated or not received as well as maybe they should have been for whatever reason?

BA: I don’t know. Nobody leaps to mind. Def Jam in the early years didn’t release very many records at all, and the records that we did release were produced thoughtfully and marketed very thoughtfully intended to be successful. LL’s records, his first four records or maybe more, they all went gold and platinum. The Beastie Boys’ first record went triple platinum, and then they left the label. Slick Rick comes out with his album and it goes platinum. Public Enemy comes out with their first record and somehow, I mean Public Enemy’s first record was a disappointment to us and only sold whatever, 300,000 to begin with. They went back to the lab and came out Nation of Millions which went platinum. That’s sort of the early history of Def Jam. Russell tried things with latter-day soul music. That kind of stuff. And that stuff never took off the way some of the rap stuff did.

I: What would you say were the happiest times at Def Jam?

BA: The whole early period. The whole time I was there was a pretty happy time. It was a pretty magical time. It was a small group of us, we went to work every day, we were kind of united by a sense of mission, we went from success to success. Not to say there weren’t crises and not to say that there weren’t attacks, not to say that there weren’t fuck-ups, but that was a golden period for me anyway. It’s the only period I had. I left in March of 1990 and that turned out to be…things were getting more corporate. Finally, the company would be sold from Columbia to Polygram in ’93, ’94. I wasn’t there during those times when the label was physically absorbed into the corporate headquarters. Not to say that working for Def Jam during those years wasn’t a wonderful thing. If you talk to Kevin Lyles or if you talk to Lyor, or you talk to Julie Greenwald; if you talk to some of the artists from that era. Talk to Red or Meth or some of them. All of them have their own stories about their era and I think similarly fondly about their time.

I: If you could talk to me a little bit about your departure and what prompted you to leave, and what did you do afterward?

BA: I left because I’d been working for Russ for over five years and I wanted a piece of the company, and Russell said absolutely not it was out of the question. I felt dissed and I was very disappointed by his obstinacy, and so I left. I formed my own PR firm. I’ve done a zillion things since then. I’ve formed my own PR firm, I formed a spoken word record label called Mouth Almighty, I opened a Hip Hop oriented art gallery called the Eye Jammie Fine Arts Gallery, I wrote and produced a five-part documentary history of Hip Hop for VH1 called And You Don’t Stop: 30 years of Hip Hop. I’ve done a variety of things. I’ve continued to write books. And, I remained friends with Russ and Lyor and the people at Def Jam.

I think probably today it’s the same situation were to emerge Russ might reconsider, but he didn’t have a dozen companies then and he wasn’t a zillionaire then. I left at kind of a low point in the label’s history. He probably literally felt he couldn’t afford to cut me in.

Lessons from the early Hip Hop music industry.

I: If you don’t mind sharing what you feel is your words was the most valuable lesson that you learned during your time at Def Jam.

BA: Well it’s going to sound like the most shop-worn, graduation day platitude, it’s just follow your heart. That’s what the label did. That’s what the artists did and that’s what the people behind the scenes did, and it’s paid off beyond anybody’s dreams. Even if it hadn’t paid off materially and popularly that it did, I still think the executives and artists involved with the label during that era, would have been happy in their work because that is the key to happiness in your work; do work that you love. It’s almost kind of more general, it’s bigger than Hip Hop. I would say you don’t have to work at Def Jam in the early ‘80s to have enjoyed happiness in your work. I think that those people who conceive of a passion in their lives and are able to follow that passion into the work-a-day world, are singularly blessed. And that’s what we had at Def Jam in the early years.

I: Awesome. And if you don’t mind sharing maybe a little-known fact about early Def Jam that most people that enjoyed the music just don’t know, or haven’t been privy to.

BA: I really enjoyed about-I learned a lot putting the book together. I guess I thought I was going to do the book as a typical third-person narrative, but when I started doing the interviews everybody was so forthcoming and so compelling on its own terms, I felt let’s do it as an oral history and let everybody tell his story in his own words.

[Regarding Cey Adams, Def Jam’s original art director:] One of the things that distinguished the label I think that there was so much attention paid to the visual marketing of the artists and the advertising looked a certain way, the album covers were fussed over, and again, that’s something wasn’t done at the Indy labels prior to that time. Or even at the major labels. Rick Rubin is somebody who obsessed over the look of an album cover. It was magical to him, it was important to him, and obviously Cey [Adams] who was a visual artist feels the same way. Let’s do something that’s true to the culture and true to the artist and is of a visual match on the same level, same high level as the music itself. We’re not just going to put out something generic.

I: Indeed, and certainly I was definitely planning to speak to Cey. Those covers are in many ways they live on forever.

BA: I mean look, its 25 years later and we’re going to reproduce some of those covers in a book that happens to be 12×12. The book itself is the dimensions of an old album cover. I will say this as an older person who sees anybody else, the future of books per se is very much in question; and having said that, I believe that there’s something to be said for an actual physical book. An image that’s twelve inches square and beautifully reproduced. I don’t think computer screens compete. Not at that level. If it’s a novel go ahead to your Ipad or your Ebook and it’s a beautiful thing. The story to be told requires beautiful pictures as well, then make an art book or so-called art book the way that Rizzoli does and glory in that because it’s still the best medium for stories like that.

I: In regards to the book, was it something you had planned to do for quite some time?

BA: No, I had no plans. That’s Lauren Wirtzer who works for Def Jam Enterprises. I believe that she led the charge and she’s the one who got the deal struck with Rizzoli and make this book. At that point, Lyor said to Lauren call Bill. And he was right you know, it’s a beautiful project for me. I’m well matched for the job.

I: Of course. What was Dan Charness’ involvement in the process?

BA: Well Dan is co-author. He wrote the second half of the history. I basically wrote the history from the early years through ’93 and the transition of Def Jam from Columbia to Polygram, and he wrote it from ’94 until the present day. He wrote that text. Dan is a guy who was on the scene, you know he’s much younger than I am, but he was on the scene very early on. He’s a guy who wrote his college thesis, he was at Boston University I think, he wrote his college thesis about hip hop in 1988 or whatever. Then he got a job working with Profile and then he got a job writing for the Source in its early years, and then he went and worked for Rick Rubin at Def American in Los Angeles, and on and on. Most recently he wrote a wonderful book, “The Big Pay Back.”

I: Sure, we interviewed him for that. I did radio back in the early ‘90’s for about a decade and he use to promote on the Hip Hop side to us.

BA: I reached out to him. As I considered the job, I couldn’t pretend that I knew the latter half of the label’s history as well as I knew the early half, the first half. So I reached out to Dan who was younger and who’d paid more attention to do that part of it.

I: If I could ask you, what do you listen to today?

BA: I listen to all kinds of stuff. I don’t listen to the radio very much, but my musical tastes continue to grow. I’m listening to not just new stuff, but I listen to older stuff too. Basically, I’m somebody who’s not just moving forward but I’ve been moving backwards as well. I’m born at a certain time. The thing about the Beatles that was so great was their roots were so evident. If you listen to what they did that absorbed all of rock-n-roll history prior to them. The Beatles led me back to a lot of the R&B that I hadn’t heard prior to that, and a lot of the country music I hadn’t heard prior to them. Even so as far back as I got was maybe to the immediate post-war era by the time I’m thirty. I’ve spent a lot of time in recent years listening to pre-war stuff. From the 20’s and 30’s, and there’s a lot to love in that as well.

I: Do you feel that there’s any label that has come close to the essence of Def Jam in its prime?

BA: I’ll say this; there should be other books along these lines. As far as I’m concerned, let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred books bloom. Tommy Boy has just celebrated its 30th anniversary. There should be a book devoted to Tommy Boy. Jive did great, great stuff. There should be a book about Sugar Hill, and a book about Enjoy Records. There really should be a book about Bobby Robinson and his whole career, what a remarkable human being. Most of his career pre-dates rap, but it includes rap. Somebody should do something on him. I guess there have been books about Dr. Dre, but all the labels he’s been involved with, what an incredible guy. A book about Master P and what he’s done. A book about Luther Campbell as a record guy.

The Cash Money Guys; goddamit there’s a book there. Rap A Lot in Houston, where’s that book? These are all tremendous stories. The question you asked me, the easy answer would be “Oh fuck everybody else, we’re the best. We’re the NY Yankees, who cares about anybody else.” I’ve never felt that way. I respect anybody. One of the things that’s so great about Hip Hop is that it’s so entrepreneurial. It’s so grassroots over and over and over again. Nobody waits to cut a deal with some conglomerate. They have a song, they get behind the mic, they make a record, they press up the record, they start to take it around themselves, they go to radio, they go to the press, they start touring. There’s your connection to the punk rock thing. DIY, that’s hip hop. I respect that impulse so much. It’s such a likable thing, “I’ve got an idea about something I want to do, and I’m going to do it. The end. I don’t need any help. I’m good.” That’s actually the story of-Dan’s book “The Big Payback” over and over again. So sure, there should be dozens and dozens more books along the lines of this Def Jam book, that’s what I believe.

I: There’s a picture in the book of you in the studio with Aerosmith and Run DMC. As a fan of Run DMC, that was such an interesting time because in many ways it, in my opinion, not being that well versed in Aerosmith’s history, I know they’d been around in the 70’s. It almost propelled them back.

BA: It did. It absolutely did.

I: And it’s kind of ironic in a way, Hip Hop wasn’t respected early on and hip hop wasn’t taken seriously, and they had to fight to get into the awards and Run DMC had been inducted into the Rock-n-Roll Hall of Fame since then, and to see that picture, you’re there, of this 70’s rock band who was brought back to life by this crew from Hollis; if you could share anything about that experience being there.

BA: It speaks again to the DJs art, the hip hop DJs art. That opening beat to “Walk This Way” was a well-known break beat to rappers and DJs throughout the city. The funny thing is that Run DMC and J had never bothered to listen; they’d never listened deep enough into this song to even hear the vocals. The vocals were extraneous to them. That opening “doomp-dack-doomp-doomp-dack-doomp-doomp-dack” so that’s a beat that’s two bars of music and they’d play it on one turntable and then cut and play the same two bars on the next turn table, and they were done. They’d had no use for the body of the song itself. Rick Rubin was somebody who’d grown up Aerosmith, and he was familiar with the song itself. He says to the guys when they’re making “Raising Hell.” He says listen we ought to cover “Walk This Way,” and the guys themselves didn’t even know or heard of a called Walk This Way. They’d never heard of Aerosmith. As far as they were concerned, the name of the group was “Toys In The Attic.” Because that was the name of the album and that’s all they remembered from it. That’s how they remembered it. It was a break beat. It’s a “Toys In The Attic” break beat was really the way they thought of it. So when it came time for them to make that record, they said okay we’ll use that beat and write some new rhymes and it’ll be a beautiful thing. Rick says, “no, no, no, no” you’re going to cover that record and you’re going to make it with the guys from Aerosmith themselves. So for the first time after having been familiar with this beat for years, they were forced to listen to the record, and Run and D were appalled. DMC famously said it sounded like hillbilly jibberish to him. He couldn’t figure out what language are they talking. What are the words? They didn’t know. They really resisted doing it. J I think was instrumental. J said listen, “this is a cool opportunity for us…fellas.” He joined in with Rick and Russ and bashed into Run and D’s brains and said fuck you guys, go home and learn the song. That’s how it was made and kind of why it was made.

Oh by the way and then one of the things is that once they all got into the studio together…it was fine. They got along very well. It was just a bunch of musicians in a room together and it was not a problem. See that’s the thing about musicians. There really is a brotherhood of musicians, civilians don’t understand it maybe. Musicians all over the world essentially speak the same language, they have the same kind of sensibility. Run and D learned something, undoubtedly the guys form Aerosmith learned something too. Whatever it was that they knew, what little they knew about hip hop, well, all of a sudden here’s Run DMC, they’re the biggest group in this new genre, and they got into the studio at the same place and the same time, and made a wonderful record. It was to Run DMC’s credit and to Aerosmith’s credit simultaneously, and everybody was happy. It was a wonderful learning experience for everybody involved I think.

I: Indeed. It’s amazing how much an impact it’s had on people, and that’s what I think about, its almost surreal to see this genre grow from almost nothing into having this kind of legacy and seeing how powerful and important the players have become is almost unbelievable, it’s almost surreal.

BA: Well except, remember I’ve always said that I think the rock mainstream was looking, it was so lame, it was so weak, it was anemic, it was ripe for plunder. It needed a bullet in the head. And somebody knew to come in and revitalize it. Good God, rock-n-roll in the 80’s, white rock-n-roll in 80’s… horrible. Luckily here comes rap, it infused it with all this new energy and humor, and on and on. It was really just what the music was looking for. Otherwise, Good God we’d be into the 60th iteration of Boy George and the Eurhythmics.

I: It’s truly a pleasure, you were always kind to me when I’d call back then. Back then I was a Puerto Rican kid from Bronx River who recorded with a Jewish kid from Brooklyn, started to record industrial metal rap, and was influenced by all of this.

BA: But again see, that’s the thing. I believe that rap kind of incidentally reintegrated American pop. That’s one of the reasons the rock in the 80’s was so anemic was because it was so racially segregated. It was buying for white people. It really was bloodless. So all of a sudden it’s not just rappers, its people of color. That made a huge, huge difference. We think about it now as if it was the most remarkable, unheard of thing in the world, and it was maybe at that moment. But you know the history, American history; history of the American pop music has always been about race mixing to the benefit of America’s music lovers. American music is a racial hybrid, it’s a mutt. And that’s what makes it so great. It was just a kind of historical anomaly that the music was segregated, at least on the radio during the 70’s. So you had rock on one side on one station, and you had whatever was going on in black music on another radio station. And that was really artificial and damaging, I believe to the young people who grew up in that era.

So when rap comes along and reintegrates popular music in the 80’s it comes as this kind of stunning revelation to the people who’d only known about white music for white people, and black music for black people. Anybody that had grown up prior to that time would say, “what’s the big deal? That’s the way it’s supposed to be.”

I: Indeed.

Interview and introduction by Israel Vasquetelle.